Here's The Programming Game You Never Asked For

You know what's universally regarded as un-fun by most programmers? Writingassembly language code.

As Steve McConnell said back in 1994:

Programmers working with high-level languages achieve better productivity and quality than those working with lower-level languages. Languages such as C++, Java, Smalltalk, and Visual Basic have been credited with improving productivity, reliability, simplicity, and comprehensibility by factors of 5 to 15 over low-level languages such as assembly and C (Brooks 1987, Jones 1998, Boehm 2000). You save time when you don't need to have an awards ceremony every time a C statement does what it's supposed to.

Assembly is a language where, for performance reasons, every individual command is communicated in excruciating low level detail directly to the CPU. As we've gone from fast CPUs, to faster CPUs, to multiple absurdly fast CPU cores on the same die, to "gee, we kinda stopped caring about CPU performance altogether five years ago", there hasn't been much need for the kind of hand-tuned performance you get from assembly. Sure, there are the occasional heroics, and they are amazing, but in terms of Getting Stuff Done, assembly has been well off the radar of mainstream programming for probably twenty years now, and for good reason.

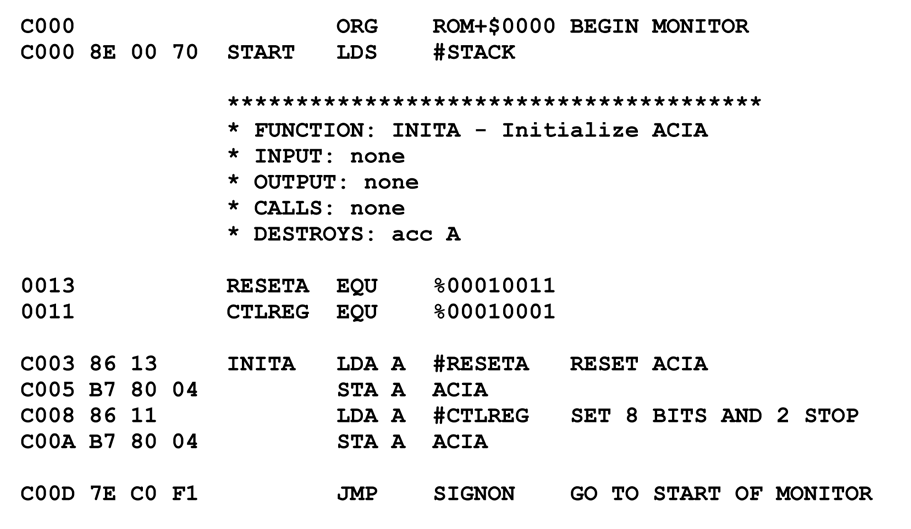

So who in their right mind would take up tedious assembly programming today? Yeah, nobody. But wait! What if I told you your Uncle Randy had just died and left behind this mysterious old computer, the TIS-100?

And what if I also told you the only way to figure out what that TIS-100 computer was used for – and what good old Uncle Randy was up to – was to read a (blessedly short 14 page) photocopied reference manual and fix its corrupted boot sequence … using assembly language?

Well now, by God, it's time to learn us some assembly and get to the bottom of this mystery, isn't it? As its creator notes, this is the assembly language programming game you never asked for!

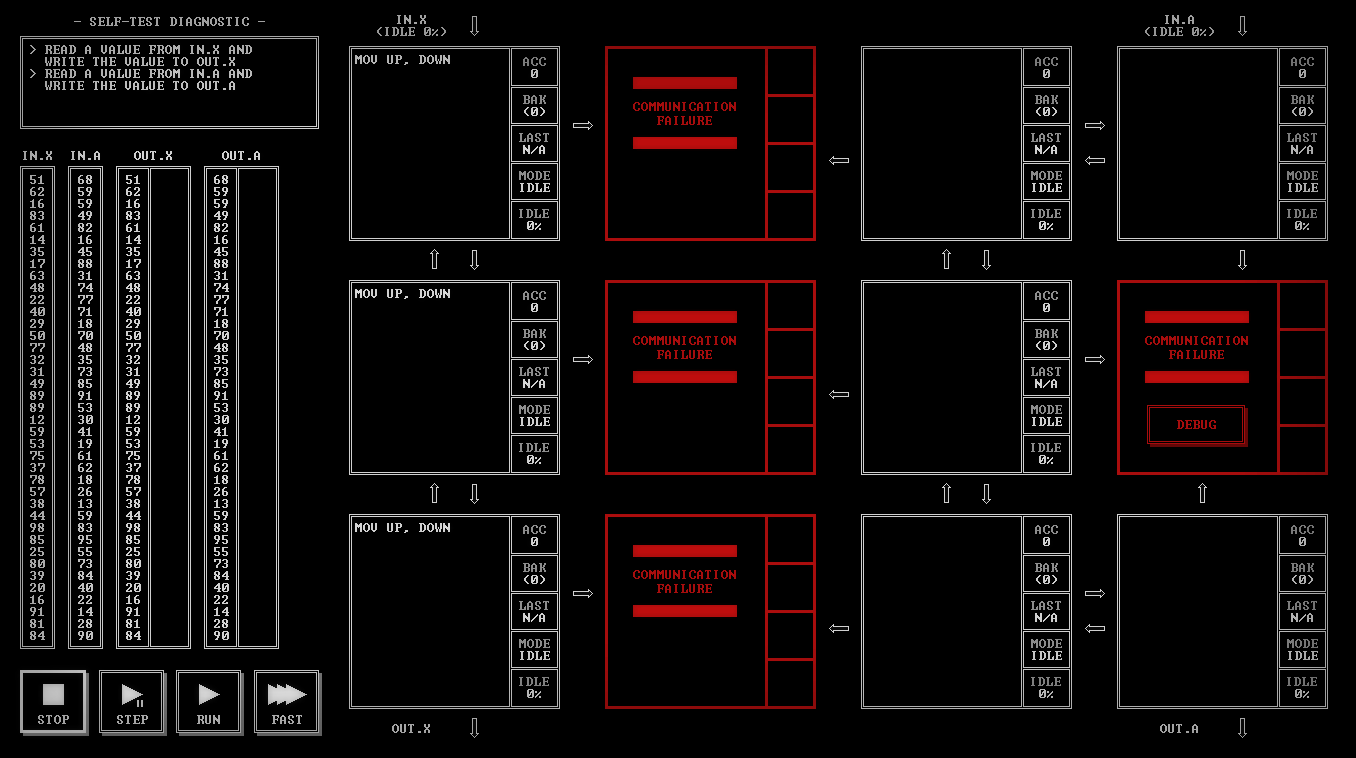

I was surprised to discover my co-founder Robin Ward liked TIS-100 so much that he not only played the game (presumably to completion) but wrote a TIS-100 emulator in C. This is apparently the kind of thing he does for fun, in his free time, when he's not already working full time with us programming Discourse. Programmers gotta … program.

Of course there's a long history of programming games. What makes TIS-100 unique is the way it fetishizes assembly programming, while most programming games take it a bit easier on you by easing you in with general concepts and simpler abstractions. But even "simple" programming games can be quite difficult. Consider one of my favorites on the Apple II, Rocky's Boots, and its sequel, Robot Odyssey. I loved this game, but in true programming fashion it was so difficult that finishing it in any meaningful sense was basically impossible:

Let me say: Any kid who completes this game while still a kid (I know only one, who also is one of the smartest programmers I’ve ever met) is guaranteed a career as a software engineer. Hell, any adult who can complete this game should go into engineering. Robot Odyssey is the hardest damn “educational” game ever made. It is also a stunning technical achievement, and one of the most innovative games of the Apple IIe era.Visionary, absurdly difficult games such as this gain cult followings. It is the game I remember most from my childhood. It is the game I love (and despise) the most, because it was the hardest, the most complex, the most challenging. The world it presented was like being exposed to Plato’s forms, a secret, nonphysical realm of pure ideas and logic. The challenge of the game—and it was one serious challenge—was to understand that other world. Programmer Thomas Foote had just started college when he picked up the game: “I swore to myself,” he told me, “that as God is my witness, I would finish this game before I finished college. I managed to do it, but just barely.”

I was happy dinking around with a few robots that did a few things, got stuck, and moved on to other games. I got a little turned off by the way it treated programming as electrical engineering; messing around with a ton of AND OR and NOT gates was just not my jam. I was already cutting my teeth on BASIC by that point and I sensed a level of mastery was necessary here that I probably didn't have and I wasn't sure I even wanted.

I'll take a COBOL code listing over that monstrosity any day of the week. Perhaps Robot Odyssey was so hard because, in the end, it was a bare metal CPU programming simulation, like TIS-100.

No comments:

Post a Comment